A Response to a Diatribe Regarding Player Values

I don’t know if y’all are familiar with Tanner Bell. He recently joined the RotoGraphs staff and has wasted no time churning out quality post after quality post. He performs analysis, but he also offers technical advice regarding the “offline” components of fantasy baseball such as building cheat sheets in Microsoft Excel. It’s good stuff, even for people who consider themselves proficient in Excel — I do and, alas, it never occurred to me to conditionally format my draft prep workbook to strike out players already drafted.

Similarly, it seems Tanner recently experienced an epiphany (or two) of his own in regard to player projections and valuations. I mentioned to him I wanted to respond, so to speak, to his post, not as a criticism but as an expansion. A validation, I guess.

Also, rarely, if ever, do we engage in back-and-forth call-and-response posts. I don’t intend for this to be one of those. It’s just that Tanner inspired me, but I have some thoughts of my own to add.

My home league drafted Saturday morning. I really like my team, but !@*$ me, I left money on the table. Again. I did this last year, and I wrote about it. I thought it wasn’t so bad, but I was wrong. So very, very wrong. My team was pitiful. Excruciatingly bad. And while 22 separate DL stints played a culprit to my team’s putrid state, my draft — and, thus, my dumb self — must bear the brunt of the blame.

This time, I do really like my team, but I can’t help but feel like I missed out on a huge opportunity because I was too stingy during the bidding for one particular player, and it completely changed the trajectory of my draft.

Projections and valuations should be fluid.

Like Tanner, I used to be a dollar-value absolutist. Rarely would you catch me bidding even a dollar over a player’s projected value, let alone two. It’s an admirable approach — you maximize your earning potential by finding bargains — but it not only can completely suffocate your draft strategy but also represents a fundamental lack of understanding of player projections.

Again, this is no criticism of Tanner. I did this, too. I did this last year. But it dawned on me — frankly, it baffles me why it didn’t sooner — that because projections represent most-likely outcomes among a distribution of outcomes, so, too, do valuations based on those projections. In other words, dollar valuations of players represent a most likely value among a distribution of values. Much of this Tanner already established.

Alas, it’s only one thing to acknowledge the fluidity of dollar values.

Determine where, within each player’s outcome distribution, his projection lies.

This is, in essence, the same advice as Determine whether each player’s value carries upside or downside. The more nuanced version of said advice goes as follows:

Player outcome distributions may not necessarily assume the shape of a normal bell curve. Some may be left- (or negatively-) skewed; others, right- (positively-) skewed. Moreover, the projection may not fall right at the mean (or average) outcome within each distribution; depending on the projection system, it might be a median projection, or perhaps it’s the most frequent, or mode, that emerges from an iterative process.

Unless a particular projection system tells you how this distribution looks or what value the projection specifically represents (Baseball Prospectus’ PECOTA technically does this, with percentage probabilities for growth and attrition), then you should consider making these determinations for yourself. Yeah — for every player. I know it’s time-consuming. And maybe you feel like you don’t really know how to make these assessments on your own — that’s why I’m using the projections, after all, you just muttered under your breath to me. If that’s the case, make use of the tools we write about here as best as possible. There are quite a few: xHR/FB, xBABIP, xK%, xBB%… the list goes on. Worst-case scenario, go by your gut.

Point is, at least have an opinion on every player and how well you think his dollar value (or ADP) captures his most-likely value, and how it compares to what you think his ceiling and floor could be.

Starling Marte has been my easiest target this preseason. FanGraphs’ Depth Charts projections pegs him for 18 home runs and 31 stolen bases, among other things. Essentially, it projects the same power output and more stolen bases (on more attempts). If you dig into his numbers, though, you see he accomplished his career-best home run total on his lowest ever hard-hit rate (Hard%) and fly ball rate (FB%). Moreover, Marte’s stolen base attempts have dropped off markedly every season, so expecting him to steal more often, at his age, is pretty bullish.

So, there. I’ve made some assessment of Marte’s projection. Relative to his average draft price/position, I think it captures his ceiling more than what has the best probability of happening. Thus, I think there’s very little room for profit and a lot of room for error.

In terms of “reliability”…

…not speaking in terms of statistical reliability, or what we might think of as “stability,” but a player’s reliability, or consistency, of performance…

Tanner covers this well. He shoots down the idea that a player’s reliability is “baked into the player’s projection” as a sensible one. This, again, all comes down to outcome distributions. The less data we have for a player, the wider his outcome distribution will be.

Bear with me, for this graphic is poorly construed.

The X-axis depicts dollar value, and the Y-axis depicts the frequency that a certain outcome will occur. In this situation, Player A (solid line) and Player B (dashed line) are projected for identical dollar values. Player A has been in the league and performing at an elite level for seven years; Player B, and the Carlos Correas of the world, debuted last year. Per their distributions, we see the probability that Player A will generate $X in value is significantly higher than Player B, even though it’s the most likely outcome for both of them. Player A’s outcome distribution is much tighter, too — at this point in his career, we pretty much know where his ceiling and floor are.

Player B, on the other hand, has a much wider distribution of outcomes. The probability that he outperforms Player A is high enough to think he’s the best thing since sliced bread. However, given he is an unknown quantity, the probability that he underperforms Player A is quite high, too. Theoretically, all of this volatility is baked into the projections, yes. But Tanner makes the argument (at the risk of putting words in his mouth) that you should be more risk-averse in early rounds, assigning a mental premium to players with tighter outcome distributions — in other words, the mor reliable ones. I support this notion, and all my recent ADP research seems to support it, too.

Value Versus Team Construction Versus Standings Gain Points

Tanner has written a lot about Standings Gain Points (SGP). Essentially, it’s a method of valuation that calculates, for each statistical category, the average difference between each team rank — say, between 1st and 2nd, between 8th and 9th, etc. It’s not exactly the average difference — the method calculates a line of best fit — but it’s close.*

(*This isn’t meant to pick on SGP specifically as a valuation method. I don’t know of any popular methods that aren’t non-linear; this one simply best helps underscore my point.)

This weekend, I made a stupid mistake: I marked Alex Gordon as kept by another team instead of Dee Gordon. This was a huge blunder, because I planned to draft two elite third basemen, outfielders, and/or second basemen. Again, it’s a keeper league, so I had in my crosshairs Manny Machado, Jose Bautista, Jose Altuve and Gordon. I passed on Machado when the bidding got too rich for my blood and bought Bautista. That left Altuve, on whom I eventually passed when the bidding passed my projected value by $3.

Except Gordon wasn’t actually available. The next-best second baseman left on the board was Robinson Cano, whom I won for $15 less than Altuve. I left $12 on the table.

A lot of this comes down to me being an idiot. But that’s not the point.

The point is Altuve was one of my best opportunities to buy speed at close to his market price. (Billy Hamilton went for way under his market price in this draft, and while I know it’s super trendy to hate drafting him, he will probably provide more value than his price for everyone who buys low on him. But I digress.) My team will very easily contend in home runs — in fact, the 20 or so that Cano will contribute to my team probably only net me two points at most in the standings.

However, in hindsight, Altuve’s could have netted me as many five points in the standings. This is my fundamental issue with SGP: it assumes an equal marginal (or incremental) value for every statistic. And this holds true for a bulk of the teams in a league. But it doesn’t capture the outliers very well. In fact, the outcomes in your league are also subject to some sort of non-linear distribution, and it’s likely the best and worst teams in each category are not subject to the SGP denominator.

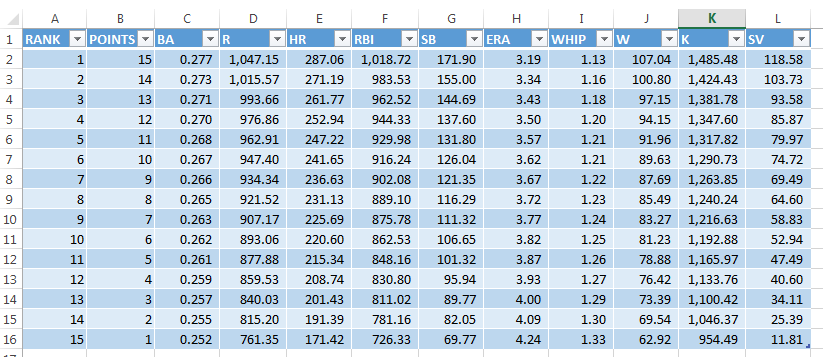

Despite denouncing SGP, which I know Tanner employs, SGP actually helps make a perfect argument for balanced roster construction. I have borrowed the following image from Tanner’s web site, Smart Fantasy Baseball.

OK. Let’s consider Altuve’s 36 stolen bases versus Cano’s 17 home runs. Looking closely at the image above, Cano’s 17 home runs best benefits a team projected to finish in the middle of the pack in the category. For example, if the 9th-place team, in terms of home runs, drafted Cano, it could mean the difference of roughly three points — 225.69 + 17 = 242.69, enough to propel the team into 6th place in the category. Those 17 home runs are borderline useless to the very worst and very best teams, though; it does not help the first- or last-place teams at all, and the 2nd- and 14th-place teams barely gain a point in the standings from Cano’s contributions, on average.

Similarly, Altuve’s 36 stolen bases are enough to boost the 9th-place team in terms of stolen bases a full six points in the category (111.32 + 36 = 147.42, good for 3rd). If the last-place stolen base team drafts Altuve? That’s worth only three points, on average.

Accordingly, a team with the best chances of gaining — and also losing — points any particular category will be a well-balanced one. The smallest differences between teams within categories most commonly occur in the middle of the pack.

There are some moving parts here; obviously, when you draft a player like Altuve, early in a draft, you don’t really know how the marginal value of his contributions will affect your team. You’re still laying the groundwork for how your team will look, statistically speaking. But when you get deeper into the draft, you need to think more carefully about these things. Tanner’s example, of Carlos Gonzalez versus Gregory Polanco, is a salient one: Gonzalez may be worth a dollar more than Polanco, perhaps. But if you stand to gain more categorical points from Polanco’s speed than CarGo’s power, then it’s Polanco, and not CarGo, who is more valuable to you at that moment in time, even if he is worth less than CarGo in absolute terms.

So… what you’re saying is, it’s all fluid. Always. Forever.

Well, kind of, yeah. You just can’t be so rigid about things. You assign values to players, but those players could, and really should, change as the draft unfolds. You should assess the relative value of other, similar players, and you should assess the value of a player mid-draft relative to the value generated by those you have already drafted. Billy Burns ain’t gonna do jack for me if I already drafted Altuve, Gordon and Hamilton, even if Burns and speed is “worth more” than Khris Davis or Joc Pederson and their respective home runs.

So that’s it. It spiraled out of control into something much bigger and longer than I ever anticipated. I think Tanner will agree with most of it. I hope he would, considering I largely agree with everything he said. I even put words in his mouth, and I agreed with those, too. I just hope it’s wasn’t too redundant or unnecessary — I just hope these small clarifications and expansions were the least bit illuminating to those of you who made it this far, that’s all.

* * *

Post script: Steamer does have reliability estimates for its projections — they’re just not included on FanGraphs. You can view 2015’s reliability estimates here, on Steamer’s website — scroll left to column AD. The hitters with the highest reliability scores? Miguel Cabrera, Mike Trout, Andrew McCutchen, Freddie Freeman, Cano, Adrian Gonzalez… surprise, surprise. For posterity, Correa’s projections ranks 1,442nd in reliability among all hitters.

My personal solution was to start calculating dollar values with, say, 90% of the actual money available. It lets me stay strict with the Alex Gordons and the Evan Longorias of the world but lets me have a petty cash box to splurge when I feel a premium is appropriate. This may not work for everyone, but it works best with my understanding of my values.