Machado’s Weird Contact

Manny Machado has been in a slump. That feels like an understatement. Over the past month he’s been one of the weakest hitters in the game, managing only .261 wOBA and 56 wRC+. This value is buoyed by six home runs, which account for 27% of his hits in the month of May. This is one of the worst stretches of his career, if not the worst. Notably, he had a rough patch to begin the 2015 season, but that period only lasted two, perhaps three weeks. It also had a reason, Machado had missed the final 80 games of 2014 while recovering from knee surgery. This year, though. This is different.

There are no obvious signs of problems with Machado. By all accounts his mechanics seem fine and he appears to be healthy. There could be psychological issues at play and many have used the term ‘pressing’ to describe Machado. Unfortunately there is a possibility that the feud with the Red Sox and the resulting beanings and attempted beanings may have played some role in his slump, although that seems like a bit of a stretch. None of these explanations are satisfactory, and they raise more questions than they answer.

Today I’m going to look at this slump in a slightly different manner, and hopefully highlight a few measurements and stats along the way that will spark your imagination. As usual, this piece is less about Manny Machado, and more about approaching baseball from a different perspective.

At A Glance Balls In Play Stats

Machado is hitting the ball as hard as ever. His Value Hit rate is hovering around 10.3-10.5% between 2016 and 2017. In other words, just about 10% of his plate appearances result in a batted ball that is an almost guaranteed extra base hit. This is very good, the league average is 5.7%. His 10.3% rate ranks 18th in the majors among batters with at least 75 balls in play, and 16th among active players, since Mike Trout and Freddie Freeman are both injured. The standard deviation is 3.3%, so his z-score is 1.39.

This is very good, but it shouldn’t be a big surprise given his home run rate this year. He has 10 homers, and he’s on pace for at least 19 more.

On the flip side, his poorly hit rate—near automatic outs—is down. Not by a terrible amount, but enough to be noticeable. It has actually been steadily dropping since 2015. Perhaps 2015 was hampered by his knee injury, perhaps it is an evolving skill. It is hard to tell since the stat isn’t available prior to 2015. Either way, it has fallen from 26.5% to 23.3% to 22.3% respectively over the past three years. This is another great thing to see, although hold onto your pants because I’ll delve deeper into this issue in a moment.

I should note that his strikeout rate has increased this year, which more than offset his decrease in poorly hit rate. You can generally lump the two together, since they are both near guaranteed outs. In this sense, his ‘automatic outs’ per plate appearances has gone up from 40% last year to 44% this year.

Alright, so that’s neat, he’s hitting the ball hard with fewer weakly hit balls. In general, you’d expect an uptick in performance, but we know he’s gone in the other direction. I guess at this point a lot of people give up and claim BABIP. Yes, he has an atrocious BABIP, but we also have more ways to examine quality of contact so let’s dig deeper.

Exit Velocity

Machado’s exit velocity is up by quite a bit, nearly 94 mph from around 90 mph last season. You might look through xStats and notice his HD velocity is up by 10 mph (!!). His flyball velocity is up by 5 mph, too. Both of these should lead to homers, probably. And he’s hit a bunch of homers, so that checks out.

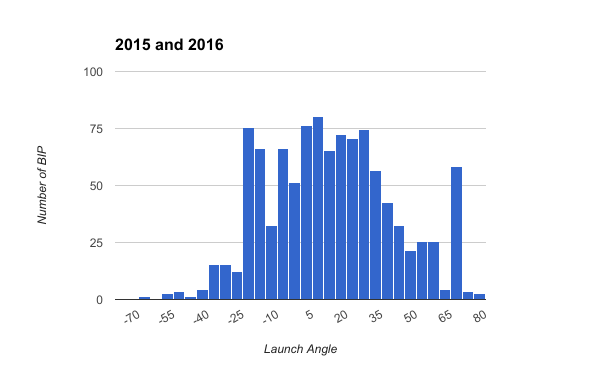

Except there really is a lot more to Exit Velocity than just averages. I think this story is best described using histograms. This first histogram contains both 2015 and 2016 data. Trust me when I say that both 2015 and 2016 each, independently, look roughly the same.

Both of these charts range from 30 to 120 mph along the x axis, so even with different labeling they are on the same scale along that axis.

In 2015 and 2016 you see a multimodal distribution, with one peak around 85 mph, and a few bumps between 90, 100, and 110. The drop in frequency below 80 mph is rapid, but somewhat smooth.

Now compare that to 2017, which appears quite different. Yes, it still has a peak around 82 or so, which might be roughly equivalent to the 85 mph peak from prior seasons. You have a few bumps between 95 and 112 or so, which roughly coincides with what we expect. However, the lower end of these exit velocities, between 30 and 80 mph, are largely missing. This probably explains his drop in poorly hit balls.

We’re Going to Need Launch Angle, Too

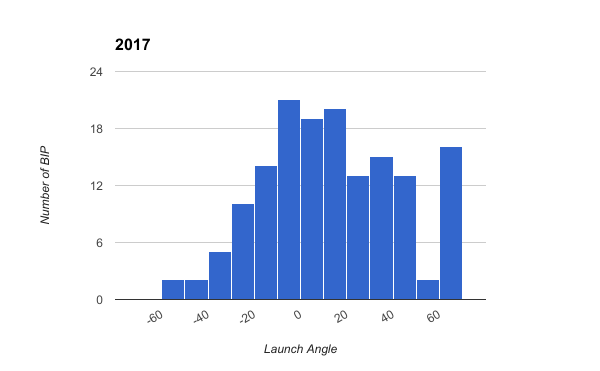

Just like the exit velocity charts, both of these launch angle charts have the same x axis. The labels are different, but they are on the same scale, from -80 to 80 degrees.

There are a few notable features in these charts. In 2015 and 2016 you have spikes in frequency between -25 and -10 degrees. I’m not sure exactly what causes this, it could be inaccuracies in the reported measurement. You also have a sort of dual peak between 5 and 30 degrees, followed by a gradual but somewhat smooth drop off as you increase towards 50 degrees.

In 2017, it is very different. There is a peak around 20 degrees, then a sudden drop between 20 and 30 degrees. The spikes in frequency between -25 and -10 degrees are also entirely missing, which may help explain the decrease in low exit velocities.

Tying it Together

Manny Machado has had a large and uncharacteristic decrease in frequency for launch angles between -25 and -10 degrees and 20 and 30 degrees. As a result, his distribution of exit velocity has become distorted. There appear to be a significant drop in the frequency of both his low value and middle value batted balls, which would likely result in a dramatic reduction in his singles rate. Meanwhile, his high end batted balls appear to have remained constant.

As a result, you see a continued source of in game power, but a large reduction in singles and batting average. This pattern is not consistent with an attempt to hit the ball into the air more often. Or rather, if he were trying to hit the ball into the air, he is clearly failing to do so, judging by the dramatic reduction in batted balls between 20 and 30 degrees. He’s hitting fewer balls into the air, but he has maintained a high exit velocity on these balls and as a result has maintained his high quality contact.

These changes, overall, appear like random variation to me. Perhaps the extreme edges of variation, maybe a worst case scenario. But nothing here seems to suggest Manny Machado has lost any raw skill, or that he is even missing the ball by very much. Rather, his launch angles just happened to have fallen into a weird distribution to start the season. This seems to be statistical variation at its finest.

That said, Machado’s xStats point towards a tinge of bad luck as well. His xStats to date suggest production much closer to his career norms.

| AVG | OBP | SLG | BABIP | wOBA | HR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| xStats | .266 | .340 | .520 | .289 | .364 | 12.5 |

| Actual | .205 | .286 | .405 | .218 | .297 | 10 |

There may be psychological components to what is going on with Machado, I can’t speak to that. Buck Showalter has stated he feels Machado’s slump may be more mental than physical. Several Orioles coaches and other MLB scouts seem to agree with that general sentiment. I’m not an expert on Machado’s mechanics (or any mechanics for that matter), but I don’t see a major problem with my own eyes.

Machado’s plate discipline doesn’t appear to have varied much, although his swinging strike rate has gone up to 12%. Pitchers are throwing him a few more sliders, and he appears to be handling sliders exceptionally poorly, but otherwise his pitch mix appears to be about the same. The pitch location data this year makes me uncomfortable, so I’m not going to look too deeply into that.

What Does A Red Flag Look Like?

As I stated up front, this article isn’t so much about Machado as it is an attempt to offer a different perspective. I’ve quoted two stats, Value Hits and Poor Hits, both of which can be found on xStats.org. I’ve also referred to exit velocity and launch angle histograms, which you can easily create yourself using baseball savant. You can apply this method to any player with very little effort.

I claim to see no red flags with Machado in this case. Rather, it is likely a small sample size problem that will straighten itself out over time. But you may be wondering what a red flag may look like, and how to search for one yourself when looking at a different player.

Note that this sort of analysis requires a decent sample size. You really want to aim for at least 100 balls in play. Having said that, first look for the maximum exit velocity. Has it decreased substantially? Say a batter’s maximum exit velocity was 117 mph, and this year, after 150 BIP, his max is only 108 mph. That would be a red flag.

Next, create a histogram as I have done above, and look at the distribution near the maximum exit velocity. You should see a rapid, but smooth drop in exit velocity. If this drop is spread out over a wide range of velocities, that is a bad sign. For example, Machado in 2015-2016 had a precipitous drop in frequency between 110 and 120 mph. This is about normal. If your batter saw a drop between 95 and 115, that would be worrying. It could point to an injury or mechanical problem that is reducing his bat speed.

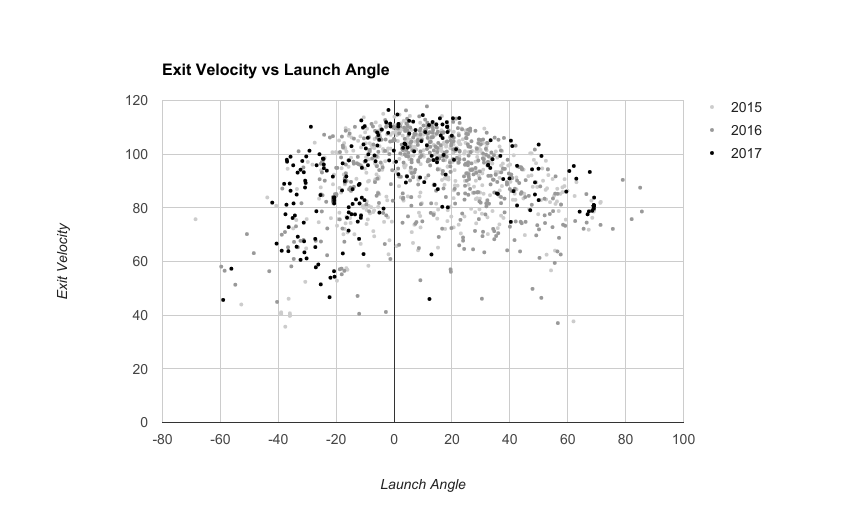

Finally, you may want to plot exit velocity versus launch angle, like you see in the chart above. I have color coded seasons, I hope they are easy enough for you to see. You can see in 2017—the black dots—the distribution is way out of whack when compared to the prior 2015 and 2016 seasons, heavily favoring ground balls. This sort of radical departure can be observed with players, although it might be more common to see it towards the fly ball end of the spectrum. This should always be viewed as a major red flag, regardless of whether it is tending towards fly balls or ground balls.

Andrew Perpetua is the creator of CitiFieldHR.com and xStats.org, and plays around with Statcast data for fun. Follow him on Twitter @AndrewPerpetua.

This is very well done. I especially appreciate how you “show your work”, as it were, by suggesting how other forms of this analysis could proceed. Good stuff.